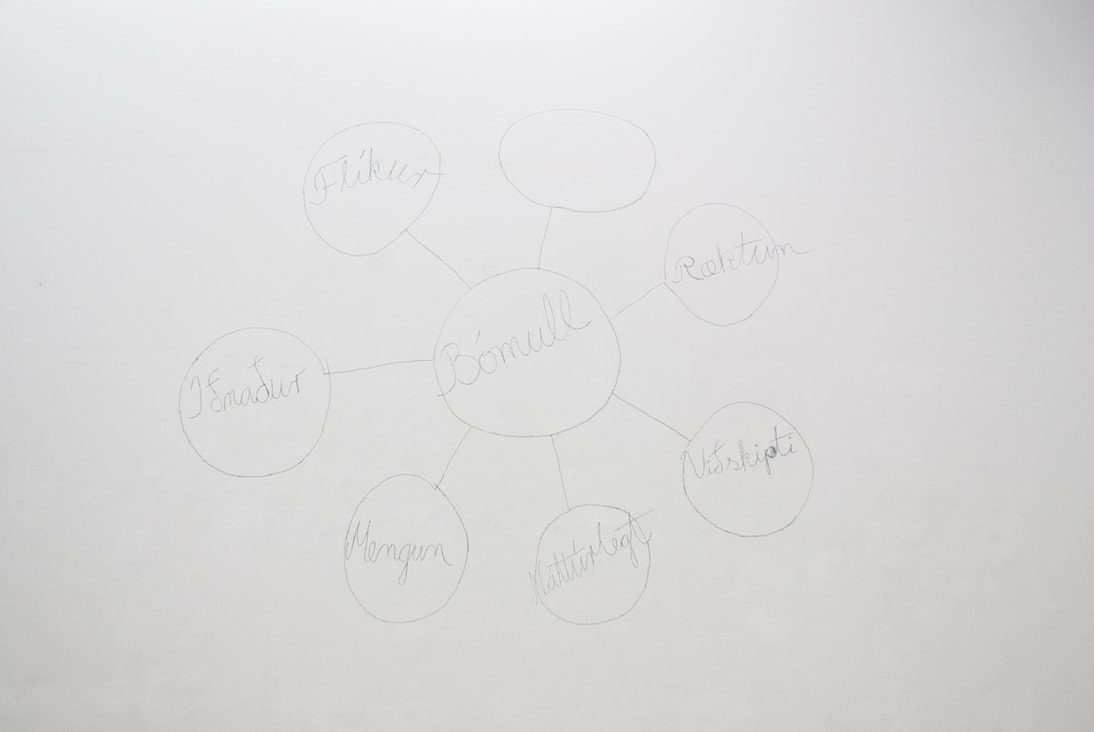

Bómullartuskur - Cotton Rags

Anna María Lind Geirsdóttir opnar sýninguna "Bómullartuskur"

laugardaginn 21. janúar 2012 kl. 13í sal Íslenskrar grafíkur Tryggvagötu 17, hafnarmegin.

Sýningin stendur til 5. febrúar og er opið fimmtudaga - sunnudaga kl. 13-18.

Fótgangandi og hjólandi gestir sérlega velkomnir

Sunnudaginn 29. janúar kl. 15 verður listamannaspjall

Ritgerð Deborah Kraak er mikilvægur hlekkur í sýningunni.

Sýningarstjóri er Magnús V. Guðlaugsson.

Anna María Lind Geirsdóttir opnar sýninguna "Bómullartuskur"

laugardaginn 21. janúar 2012 kl. 13í sal Íslenskrar grafíkur Tryggvagötu 17, hafnarmegin.

Sýningin stendur til 5. febrúar og er opið fimmtudaga - sunnudaga kl. 13-18.

Fótgangandi og hjólandi gestir sérlega velkomnir

Sunnudaginn 29. janúar kl. 15 verður listamannaspjall

Ritgerð Deborah Kraak er mikilvægur hlekkur í sýningunni.

Sýningarstjóri er Magnús V. Guðlaugsson.

About Cotton by Deborah Kraak

Cotton is a natural, cellulosic fiber with an ancient and international history of cultivation, production, and trade.

Native to many tropical and subtropical regions, including Peru, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa, it is most closely associated with India. Archaeological finds date Indian cotton spinning, weaving and dyeing to around 3000 BCE. The Greek historian, Herodotus (5th century BCE), writing about the cotton plant, described the Indian shrub’s fluffy cotton bolls as tree wool, 'surpassing in beauty and in quality the wool of sheep; and the Indians wear clothing from these trees.’ The Romans were enthusiastic importers of Indian cottons, especially prizing the lightweight muslins the Indians called woven wind. For centuries, Indian artisans knew best how to convert the short cotton fibers (known as staples) into yarns strong enough to be used for warps. They also knew how to pattern the cotton cloth with colorfast colors, a process unknown to Europeans until the late 17th century. The West later dominated world cotton production, with machines to separate the cotton fibers from their numerous seeds and to mechanize warp spinning. These inventions and the huge demand for printed cotton drove the Industrial Revolution and changed history. Today, cotton remains an international product, and cotton fabrics are still prized for being comfortable to wear.

Modern technologies have been developed to meet the perennial challenges of growing and producing cotton. Some of these have high environmental costs, particularly pesticides and dyes. Cotton accounts for approximately 10-16% of the world-wide use of pesticides (including herbicides, insecticides, and defoliants) and between 16-25% of insecticides. (The figures are disputed by the cotton industry.) The dyeing process pollutes water. Alternatives are being sought by concerned scientists and environmentalist. Pesticides can be reduced through selective breeding for a more insect-resistant cotton and the use of organic methods of cultivation and pest control. New dye technology is being explored, as well as the hybridizing of naturally-colored cotton fibers. Consumer awareness also helps drive the search for a more organic, responsible cotton product. Recycling and restyling cotton clothing and fabrics are creative ways to reduce the demand for new cotton goods.

Cotton is grown all over the world today. Sometimes cottons from certain areas are known for their particular beauty. Sea Island cotton, grown on the coastal islands of South Carolina and Georgia in the United States, have a staple approximately 1 3/8“ or longer. Because their yarns don‘t need to be as tightly twisted, they produce a more lustrous and supple fabric. Long-staple cottons supply the luxury end of the trade.

After spinning, cotton yarns are woven or knitted into fabrics which are then dyed or printed. Production is now global, often from the industrially developing parts of the world. Even a simple T-shirt may be the work of several countries‘ labors: to grow the cotton, spin it, weave it, cut it into pattern pieces, and fashion it into a garment.

Cotton is a natural, cellulosic fiber with an ancient and international history of cultivation, production, and trade.

Native to many tropical and subtropical regions, including Peru, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa, it is most closely associated with India. Archaeological finds date Indian cotton spinning, weaving and dyeing to around 3000 BCE. The Greek historian, Herodotus (5th century BCE), writing about the cotton plant, described the Indian shrub’s fluffy cotton bolls as tree wool, 'surpassing in beauty and in quality the wool of sheep; and the Indians wear clothing from these trees.’ The Romans were enthusiastic importers of Indian cottons, especially prizing the lightweight muslins the Indians called woven wind. For centuries, Indian artisans knew best how to convert the short cotton fibers (known as staples) into yarns strong enough to be used for warps. They also knew how to pattern the cotton cloth with colorfast colors, a process unknown to Europeans until the late 17th century. The West later dominated world cotton production, with machines to separate the cotton fibers from their numerous seeds and to mechanize warp spinning. These inventions and the huge demand for printed cotton drove the Industrial Revolution and changed history. Today, cotton remains an international product, and cotton fabrics are still prized for being comfortable to wear.

Modern technologies have been developed to meet the perennial challenges of growing and producing cotton. Some of these have high environmental costs, particularly pesticides and dyes. Cotton accounts for approximately 10-16% of the world-wide use of pesticides (including herbicides, insecticides, and defoliants) and between 16-25% of insecticides. (The figures are disputed by the cotton industry.) The dyeing process pollutes water. Alternatives are being sought by concerned scientists and environmentalist. Pesticides can be reduced through selective breeding for a more insect-resistant cotton and the use of organic methods of cultivation and pest control. New dye technology is being explored, as well as the hybridizing of naturally-colored cotton fibers. Consumer awareness also helps drive the search for a more organic, responsible cotton product. Recycling and restyling cotton clothing and fabrics are creative ways to reduce the demand for new cotton goods.

Cotton is grown all over the world today. Sometimes cottons from certain areas are known for their particular beauty. Sea Island cotton, grown on the coastal islands of South Carolina and Georgia in the United States, have a staple approximately 1 3/8“ or longer. Because their yarns don‘t need to be as tightly twisted, they produce a more lustrous and supple fabric. Long-staple cottons supply the luxury end of the trade.

After spinning, cotton yarns are woven or knitted into fabrics which are then dyed or printed. Production is now global, often from the industrially developing parts of the world. Even a simple T-shirt may be the work of several countries‘ labors: to grow the cotton, spin it, weave it, cut it into pattern pieces, and fashion it into a garment.