Gallabuxur og bolir / Blue Jeans and Tshirts

sýning / exhibition

SÍM salurinn Hafnarstræti 16, Reykjavík

6. 1. - 24.1. 2014 opið virka daga kl. 10 - 16

Blue Jeans and T-Shirts: From the Workforce to the Catwalk and Beyond

Deborah Kraak and David Rickman

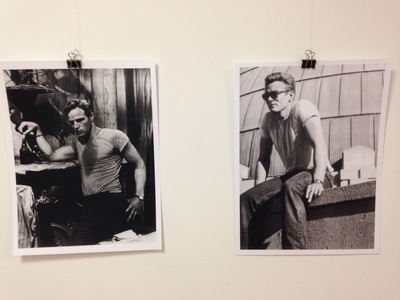

When the young and beautiful Marlon Brando gave a sizzling performance in the 1951 film A Streetcar Named Desire while wearing a tight white T-shirt and low-slung blue jeans, these working men’s garments went from being rugged, practical, and ordinary to sexy, dangerous, and special. But the path from work clothes for men to the daily dress of men and women around the world was a long one.

The history of jeans and T-shirts goes back to the early-1800s. Knitted shirts became popular the 1820s; first with the sailor’s striped, long-sleeved jerseys that were soon worn by sports players. Red or white knitted undershirts were in use by the 1840s and by the 1880s there were white, short-sleeved or sleeveless cotton T-shirts. American working men wore pants made of strong, twilled cotton that was often dyed indigo blue. San Francisco the dry goods merchant Levi Strauss made his fortune selling them. By the 1920s, cowboys and blue jeans became synonymous through Western movies, traveling rodeos and at resorts called “dude ranches,” where tourists got to dress as cowboys. But it took World War II to bring T-shirts and jeans together. Millions of American men served in the Army and the Navy and came to like the comfort and convenience of the T-shirts and the blue or olive drab fatigue uniforms they were issued. After the war, many veterans continued to wear T-shirts and jeans, including those who joined the newly-popular motorcycle clubs.

“Bikers”—often seen as being outside the law and convention—paired their rolled-cuff jeans and t-shirts with leather jackets, as Brando did in The Wild One (1953), with the classic response “Whaddaya got?” to the question “What are you rebelling against?” With the wardrobe of James Dean in Rebel without a Cause (1955), jeans (also known as dungarees or Levi’s) and t-shirts came to have a special significance for teenagers—their clothing, their sign of rebellion. James Dean “wannabees” copied his cool by folding a packet of cigarettes into a T-shirt sleeve. T-shirts and jeans were adopted by early rock ‘n’ rollers, like Elvis Presley, worn with pompadour hairstyles and a swagger. In the 1960s jeans were part of the American or European protestor’s wardrobe, later embellished with hand-embroidered peace signs. Tie-dyed t-shirts were associated with psychedelics and carried the whiff of forbidden substances.

During much of the 1960s and early 1970s, blue jeans and T-shirts became the basic outfit of teens—overlaid with whatever was currently in vogue: leather vests, fringes, ponchos, beads, and scarves. They were still considered casual wear, not quite shaking the association with manual labor, in the case of jeans, or underwear, in the case of T-shirts.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that jeans came out of the closet as a fashion garment, accepted almost everywhere, with the craze for “designer jeans”, which were emblazoned across the waistband or back pocket with the name of the designer or manufacturer. These could be worn to the disco or bars. No longer the bell-bottoms of the preceding era, these jeans were skin tight. Their high prices reflected their new status and acceptability, which they still enjoy. While today’s consumer can buy relatively inexpensive jeans at department stores, there is a huge market for specialty brands and styles. Later fashions for jeans have included tears (which is now done by design, not by chance), stone or acid washing, and “jeggings”—jeans-styled stretch pants.

Conversely, jeans—slashed and distressed—were worn by punk rockers of the late 70s, paired with equally slashed or ripped T-shirts, often held together by safety pins. The punk style influenced many fashion designers, as documented by curator Andrew Bolton in the 2013 exhibition “Punk: Chaos to Couture” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Beginning in the 1980s British designer Katharine Hamnett made t-shirts the vehicle for political statements, including nuclear disarmament and the Iraq war.

From American working men’s clothes to everyone’s clothes, the T-shirt and jeans have spread world-wide, still trailing their mid-20th century associations of counter-culture cool and protest.

Deborah Kraak is an independent museum consultant, specializing in textiles and costumes. David Rickman writes and illustrates works about the clothing of the American West.

Deborah Kraak and David Rickman

When the young and beautiful Marlon Brando gave a sizzling performance in the 1951 film A Streetcar Named Desire while wearing a tight white T-shirt and low-slung blue jeans, these working men’s garments went from being rugged, practical, and ordinary to sexy, dangerous, and special. But the path from work clothes for men to the daily dress of men and women around the world was a long one.

The history of jeans and T-shirts goes back to the early-1800s. Knitted shirts became popular the 1820s; first with the sailor’s striped, long-sleeved jerseys that were soon worn by sports players. Red or white knitted undershirts were in use by the 1840s and by the 1880s there were white, short-sleeved or sleeveless cotton T-shirts. American working men wore pants made of strong, twilled cotton that was often dyed indigo blue. San Francisco the dry goods merchant Levi Strauss made his fortune selling them. By the 1920s, cowboys and blue jeans became synonymous through Western movies, traveling rodeos and at resorts called “dude ranches,” where tourists got to dress as cowboys. But it took World War II to bring T-shirts and jeans together. Millions of American men served in the Army and the Navy and came to like the comfort and convenience of the T-shirts and the blue or olive drab fatigue uniforms they were issued. After the war, many veterans continued to wear T-shirts and jeans, including those who joined the newly-popular motorcycle clubs.

“Bikers”—often seen as being outside the law and convention—paired their rolled-cuff jeans and t-shirts with leather jackets, as Brando did in The Wild One (1953), with the classic response “Whaddaya got?” to the question “What are you rebelling against?” With the wardrobe of James Dean in Rebel without a Cause (1955), jeans (also known as dungarees or Levi’s) and t-shirts came to have a special significance for teenagers—their clothing, their sign of rebellion. James Dean “wannabees” copied his cool by folding a packet of cigarettes into a T-shirt sleeve. T-shirts and jeans were adopted by early rock ‘n’ rollers, like Elvis Presley, worn with pompadour hairstyles and a swagger. In the 1960s jeans were part of the American or European protestor’s wardrobe, later embellished with hand-embroidered peace signs. Tie-dyed t-shirts were associated with psychedelics and carried the whiff of forbidden substances.

During much of the 1960s and early 1970s, blue jeans and T-shirts became the basic outfit of teens—overlaid with whatever was currently in vogue: leather vests, fringes, ponchos, beads, and scarves. They were still considered casual wear, not quite shaking the association with manual labor, in the case of jeans, or underwear, in the case of T-shirts.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that jeans came out of the closet as a fashion garment, accepted almost everywhere, with the craze for “designer jeans”, which were emblazoned across the waistband or back pocket with the name of the designer or manufacturer. These could be worn to the disco or bars. No longer the bell-bottoms of the preceding era, these jeans were skin tight. Their high prices reflected their new status and acceptability, which they still enjoy. While today’s consumer can buy relatively inexpensive jeans at department stores, there is a huge market for specialty brands and styles. Later fashions for jeans have included tears (which is now done by design, not by chance), stone or acid washing, and “jeggings”—jeans-styled stretch pants.

Conversely, jeans—slashed and distressed—were worn by punk rockers of the late 70s, paired with equally slashed or ripped T-shirts, often held together by safety pins. The punk style influenced many fashion designers, as documented by curator Andrew Bolton in the 2013 exhibition “Punk: Chaos to Couture” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Beginning in the 1980s British designer Katharine Hamnett made t-shirts the vehicle for political statements, including nuclear disarmament and the Iraq war.

From American working men’s clothes to everyone’s clothes, the T-shirt and jeans have spread world-wide, still trailing their mid-20th century associations of counter-culture cool and protest.

Deborah Kraak is an independent museum consultant, specializing in textiles and costumes. David Rickman writes and illustrates works about the clothing of the American West.

Art from T-shirts and jeans: The alchemy of weaving

Karl Aspelund

Weaving is an alchemical exercise, as we see in old tales: Magical dwarves weave straw into gold, tricksters weave air into an emperor’s conceit, and norns weave entrails and blood into destiny. For the rest of us, simple matter –fibers from plants, animals, and the Earth itself— have for centuries been woven into creations that help form our identities, hierarchies, and symbols of status and power. Delicate, protective, evocative, and provocative, our woven garments and furnishings become a part of who we are as individuals, groups, and cultures.

Few items of clothing have had as dramatic a transformation as t-shirts and jeans. The past century contains an arc describing a path on which these garments are co-opted twice. First the hidden and uncouth basics of male laborers become the manifestations of rebellious aggression of counter-culture: Erotic as masculine and androgynous all at once. Then, tamed by corporate marketing, the symbolic fashions of disaffected youth become fetishized commodities of labels, branding, and high-fashion status, separating safely into male and female again. The base fiber, the cotton, becomes gold made by unseen hands in faraway factories in unknown places. But the gold is also still straw: The garments themselves have become basic standard elements of a global identity of nowhere, and our consumption habits now provide mountains of discarded t-shirts and jeans, languishing in containers and warehouses, shipped to impoverished communities for a second round of life. (Says our international late-modern culture: “I went global, and all I got were these t-shirts.”)

The recycling and repurposing of elements of style and fashion is in itself becoming a sign of our times and t-shirts and jeans, these base-materials of modern industrialized identity, find yet another incarnation in Anna María Geirsdóttir’s art. Rendered into basic elements of torn strips of cotton, the elemental material of our consumer fashion-culture has been rearranged into compelling constructions, inspired by stories, pop-culture, and music of days gone by. Anna María closes a circle with her work, bringing the ancient craft and poetic vision into the foreground of our attention by weaving ephemeral, worn, and discarded matter into works that are magical, colorful, and mysterious, but also practical, traditional, and tactile. A comforting sense of texture and pattern , style and function, familiar and known, is there alongside a sense of adventure and personality. (Where did the fabrics come from? Who wore them? When? Why were they discarded and how on Earth did they wind up here?) It would be magic, but magic is the excercise and application of unknown forces. The fact that alchemists were mistaken for magicians was a result of their harnessing of chemistry and physics to a degree far beyond common understanding. We would do well to understand that the objects in our daily lives can become magical if we consider them as the result of creativity and allow the magic of their history to speak. The basic elements of our daily lives, the fabrics that touch us, are not there to be thrown away. They are there to become new magic, colorful, strange and sensual objects speaking of times and places far away. Which is exactly what Anna Maria’s do: They elevate our senses with new life cunningly conjured up on the loom of the alchemical weaver.

Karl Aspelund

Weaving is an alchemical exercise, as we see in old tales: Magical dwarves weave straw into gold, tricksters weave air into an emperor’s conceit, and norns weave entrails and blood into destiny. For the rest of us, simple matter –fibers from plants, animals, and the Earth itself— have for centuries been woven into creations that help form our identities, hierarchies, and symbols of status and power. Delicate, protective, evocative, and provocative, our woven garments and furnishings become a part of who we are as individuals, groups, and cultures.

Few items of clothing have had as dramatic a transformation as t-shirts and jeans. The past century contains an arc describing a path on which these garments are co-opted twice. First the hidden and uncouth basics of male laborers become the manifestations of rebellious aggression of counter-culture: Erotic as masculine and androgynous all at once. Then, tamed by corporate marketing, the symbolic fashions of disaffected youth become fetishized commodities of labels, branding, and high-fashion status, separating safely into male and female again. The base fiber, the cotton, becomes gold made by unseen hands in faraway factories in unknown places. But the gold is also still straw: The garments themselves have become basic standard elements of a global identity of nowhere, and our consumption habits now provide mountains of discarded t-shirts and jeans, languishing in containers and warehouses, shipped to impoverished communities for a second round of life. (Says our international late-modern culture: “I went global, and all I got were these t-shirts.”)

The recycling and repurposing of elements of style and fashion is in itself becoming a sign of our times and t-shirts and jeans, these base-materials of modern industrialized identity, find yet another incarnation in Anna María Geirsdóttir’s art. Rendered into basic elements of torn strips of cotton, the elemental material of our consumer fashion-culture has been rearranged into compelling constructions, inspired by stories, pop-culture, and music of days gone by. Anna María closes a circle with her work, bringing the ancient craft and poetic vision into the foreground of our attention by weaving ephemeral, worn, and discarded matter into works that are magical, colorful, and mysterious, but also practical, traditional, and tactile. A comforting sense of texture and pattern , style and function, familiar and known, is there alongside a sense of adventure and personality. (Where did the fabrics come from? Who wore them? When? Why were they discarded and how on Earth did they wind up here?) It would be magic, but magic is the excercise and application of unknown forces. The fact that alchemists were mistaken for magicians was a result of their harnessing of chemistry and physics to a degree far beyond common understanding. We would do well to understand that the objects in our daily lives can become magical if we consider them as the result of creativity and allow the magic of their history to speak. The basic elements of our daily lives, the fabrics that touch us, are not there to be thrown away. They are there to become new magic, colorful, strange and sensual objects speaking of times and places far away. Which is exactly what Anna Maria’s do: They elevate our senses with new life cunningly conjured up on the loom of the alchemical weaver.

|

|

|

Vefnaður og list. Gallabuxur og Bolir. Gullgerð og galdur

Karl Aspelund

Að vefa er list á við gullgerð, sem sjá má í þjóðsögum og ævintýrum. Kynngimagnaðir dvergar vefa gull úr stráum, hrappar vefa hroka keisarans úr engu og nornir vefa örlög úr iðrum og blóði. Við hin vefjum okkur trefjum úr jurta- dýra- og steinaríki Jarðar. Vefir þessir hafa öldum saman skapað okkur persónueinkenni, og tákn valda, stétta og stiga. Fínleg, umlykjandi, táknræn og dulúðug, verða klæði og dúkar hluti af okkur sem einstaklingar, hópar og menningarheildir.

Það eru ekki margar klæðagerðir sem hafa gengið undir aðrar eins breytingar og gallabuxur og bolir. Öldin sem leið geymir ferli þar sem eðli þeirra var umbylt í tvígang. Fyrst varð hulinn og grófur fatnaður verkamanna að tákni uppreisnaranda þar sem öflug erótík birtist samtímis í hannaðri karlmennsku kvikmynda og í tvíkynja ímynd utangarðsmenningar. Síðan var orkan tamin af kaupmennsku verslunarmenningar og táknræn andófstíska æskunnar varð blæti vörumerkja, auglýsingamennsku og stöðutákna, þar sem kynin urðu aðgreind enn á ný í örugg hólf. Frumefni fatanna, bómullin, verður að gulli í ósýnilegum höndum í ókunnum löndum. En gullið er samt enn bara strá. Flíkurnar hafa orðið að frumeinkennum alþjóðlegra einkenna menningar sem býr hvergi. Neysluvenjur okkar búa til fjöll af notuðum bolum og buxum, sem liggja í vöruskemmum og eru flutt til fátækra landa til en lifna við. (Vestræn menning varð alþjóðleg, ferðaðist um allan heim og skilaði af sér einföldum minjagripum...)

Endurvinnsla og endurnotkun tískuvöru í hluta eða heild er að verða tímana tákn á okkar dögum. Í listsköpun Önnu Maríu Geirsdóttur öðlast frumefni persónueinkenna iðnvædds þjóðfélags nýtt líf. Þegar búið er að rífa flíkurnar niður í ræmur býr hún til hrífandi verk, innblásin af tónlist, skemmtanaiðnaði, og tónlist liðinna ára. Anna María lokar hring með verkum sínum. Hún setur fornt handverk og ljóðræna sýn í forgrunnin með því að vefa skammlífa, snjá og yfirgefna að vefa skammlífa and tactile. rð alþjjog buxum, sem liggja r aileddernism already framed the approach.ða og yfirgefna hluti í verk sem eru göldrótt, litrík og dularfull, en á sama tíma hagnýt, hefðbundin og áþreifanleg, notalega að sjá og snerta, skiljanleg í notkun og útliti. En þau bjóða einnig upp á ævintýri og persónulegar sögur. (Hvaðan komu efnin? Hver klæddist fötunum? Hvar og hvernær varð það gert? Hvers vegna var þeim fargað og hvernig í ósköpunum enduðu þau hér?) Þetta væri galdur, ef galdur væri ekki beiting og notkun ókunnra afla. Gullgerðarmenn liðinna alda voru álitnir göldróttir þegar þeri beittu fyrir sér efna- og eðlisfræði sem almenn þekking náði ekki að umvefja. Okkur ber að skilja að allt umhverfis okkur eru hlutir sem geta orðið kynngimagnaðir ef við áttum okkur á sköpunargleðinni sem gat þá af sér og við gefum magnaðri sögu þeirra gaum. Frumefni hvunndagsins, sem liggja næst okkur og umvefja, ætti því ekki að farga. Heldur ættu þau að lifna í nýjum galdri, litrík, skringileg og nautnaleg og segja okkur frá fjarlægum stöðum og löngu liðnum stundum. Það er nákvæmlega það sem verk Önnu Maríu gera: Þau efla skynjun okkar með nýju lífi sem hefur, líkt og í gullgerð, vaknað á vefstólnum.

Karl Aspelund

Að vefa er list á við gullgerð, sem sjá má í þjóðsögum og ævintýrum. Kynngimagnaðir dvergar vefa gull úr stráum, hrappar vefa hroka keisarans úr engu og nornir vefa örlög úr iðrum og blóði. Við hin vefjum okkur trefjum úr jurta- dýra- og steinaríki Jarðar. Vefir þessir hafa öldum saman skapað okkur persónueinkenni, og tákn valda, stétta og stiga. Fínleg, umlykjandi, táknræn og dulúðug, verða klæði og dúkar hluti af okkur sem einstaklingar, hópar og menningarheildir.

Það eru ekki margar klæðagerðir sem hafa gengið undir aðrar eins breytingar og gallabuxur og bolir. Öldin sem leið geymir ferli þar sem eðli þeirra var umbylt í tvígang. Fyrst varð hulinn og grófur fatnaður verkamanna að tákni uppreisnaranda þar sem öflug erótík birtist samtímis í hannaðri karlmennsku kvikmynda og í tvíkynja ímynd utangarðsmenningar. Síðan var orkan tamin af kaupmennsku verslunarmenningar og táknræn andófstíska æskunnar varð blæti vörumerkja, auglýsingamennsku og stöðutákna, þar sem kynin urðu aðgreind enn á ný í örugg hólf. Frumefni fatanna, bómullin, verður að gulli í ósýnilegum höndum í ókunnum löndum. En gullið er samt enn bara strá. Flíkurnar hafa orðið að frumeinkennum alþjóðlegra einkenna menningar sem býr hvergi. Neysluvenjur okkar búa til fjöll af notuðum bolum og buxum, sem liggja í vöruskemmum og eru flutt til fátækra landa til en lifna við. (Vestræn menning varð alþjóðleg, ferðaðist um allan heim og skilaði af sér einföldum minjagripum...)

Endurvinnsla og endurnotkun tískuvöru í hluta eða heild er að verða tímana tákn á okkar dögum. Í listsköpun Önnu Maríu Geirsdóttur öðlast frumefni persónueinkenna iðnvædds þjóðfélags nýtt líf. Þegar búið er að rífa flíkurnar niður í ræmur býr hún til hrífandi verk, innblásin af tónlist, skemmtanaiðnaði, og tónlist liðinna ára. Anna María lokar hring með verkum sínum. Hún setur fornt handverk og ljóðræna sýn í forgrunnin með því að vefa skammlífa, snjá og yfirgefna að vefa skammlífa and tactile. rð alþjjog buxum, sem liggja r aileddernism already framed the approach.ða og yfirgefna hluti í verk sem eru göldrótt, litrík og dularfull, en á sama tíma hagnýt, hefðbundin og áþreifanleg, notalega að sjá og snerta, skiljanleg í notkun og útliti. En þau bjóða einnig upp á ævintýri og persónulegar sögur. (Hvaðan komu efnin? Hver klæddist fötunum? Hvar og hvernær varð það gert? Hvers vegna var þeim fargað og hvernig í ósköpunum enduðu þau hér?) Þetta væri galdur, ef galdur væri ekki beiting og notkun ókunnra afla. Gullgerðarmenn liðinna alda voru álitnir göldróttir þegar þeri beittu fyrir sér efna- og eðlisfræði sem almenn þekking náði ekki að umvefja. Okkur ber að skilja að allt umhverfis okkur eru hlutir sem geta orðið kynngimagnaðir ef við áttum okkur á sköpunargleðinni sem gat þá af sér og við gefum magnaðri sögu þeirra gaum. Frumefni hvunndagsins, sem liggja næst okkur og umvefja, ætti því ekki að farga. Heldur ættu þau að lifna í nýjum galdri, litrík, skringileg og nautnaleg og segja okkur frá fjarlægum stöðum og löngu liðnum stundum. Það er nákvæmlega það sem verk Önnu Maríu gera: Þau efla skynjun okkar með nýju lífi sem hefur, líkt og í gullgerð, vaknað á vefstólnum.